When people speak of the body, I find they mostly mean “body” in the physical sense: organs and sinew and genetic makeup. But for me, my recently diagnosed mental illness and lingering grief are just as much a part of my body as my blood and my bones. Body, to me, is similar to identity or the sum of all the parts that make me me and you you, and our mind—and what goes on there—is a large part of that.

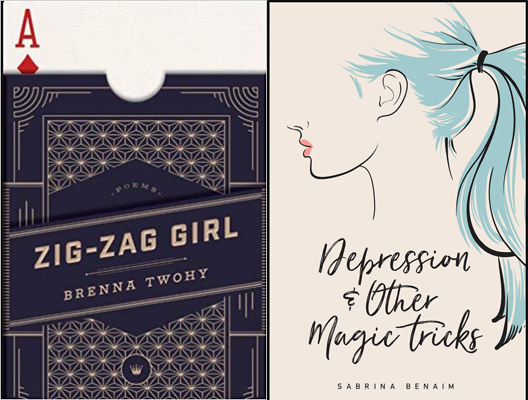

Poets Sabrina Benaim and Brenna Twohy address these aspects of body in their most recent books: Depression & Other Magic Tricksand Zig-Zag Girl, respectively. Depression and grief and just pure emotions are presented and explored in these poems—how they affect your attempts at living your life, how they can be or become part of who you are. While each book focuses more on one of these that the other (Benaim on depression/mental illness; Twohy on grief/emotion), they are doing similar work with their interpretations of the body.

Depression & Other Magic Tricks

I found Benaim’s book via a video on Button Poetry’s Facebook page. It was a recording of the poet sharing her poem “explaining my depression to my mother a conversation,” and it entranced me. “mom,/my depression is a shape shifter;/one day it is as small as a firefly in the palm of a bear,/the next, it’s the bear./those days i play dead until the bear leaves me alone.” (pg 6) Her poem so clearly presented what it feels like to have depression and anxiety, in ways I’ve been unable to put into words for those who have not experienced it themselves, that I followed the link to order her book immediately. When it arrived, I was not disappointed with the rest of her poems. While “explaining my depression” is not the opening poem to the book, it still works to encapsulate the book as a whole: a young woman attempting to understand this part of her identity, of her body. “mom still doesn’t understand./mom,/can’t you see?/neither do i.” (pg 8)

Utilizing various forms (prose poetry, erasure, spoken word), the book follows the progression of living with a mental illness and coming to terms with it being part of yourself, part of your body and your identity, to it’s conclusion. The final poem of the book, “follow-up a prayer/a spell,” shows the speaker of the collection more at peace: “i am feeling better/so i say/good morning/& mean it//yes/today/is a good morning/to exhale/to feel joy//with the release of breath/i no longer need to be holding” (pg 69). The speaker is not fixedor cured, because that’s not how depression works, but she is better, for now. She’s accepting help in all forms (“if i need more help i will let the people offering help me//if i need more help i will let the medication help me/i forgive my body for being a machine after all”) and realizing that as a part of her body, she can live with it. And the moment is beautiful.

Zig-Zag Girl

Twohy’s book caught me with the opening poem “A Coworker Asks Me If I Am Sad, Still,” a wonderfully poignant piece about grief, but also could be read as speaking about depression, and often the two are friends and bedmates. “A Coworker Asks Me If I Am Sad, Still/& I tell her,//grief is not a feeling,/but a neighborhood.//this is where I come from/everyone I love still lives there.” (pg 9) The book is segmented into three sections (Zig, Zag, and Girl), but as a whole it focuses on various types of grief—loss of a sibling, possibly to suicide; loss of love, even though it was with someone you shouldn’t’ve been, possibly toxic and misguided—with undertones of mental illness and womanhood.

Section 1, Zig, is clearly focused on the loss of a brother at an age where it’s unexpected. But the other two start to merge these themes together, showing how all of it can become entangled in each other. How it can become entangled in yourself. Section 3, Girl, shows recovery of what can be recovered from, and acceptance of what cannot. The ending couple of poems, “I Am Not Clinically Crazy Anymore” and “when the crazy came back” encapsulate what it’s like to have a mental illness, to have intense grief, and how you push yourself to keep going. “this body knows withstand. knows/what the morning looks like when she says stay.//the crazy/is a quitter.//you have a perfect/attendance record for this life.//& I will stay./& I will stay.” (pg 52-53)

I’m not sure if Benaim and Twohy would say they wrote poetry of the body in these books if asked, but I think they did. And they did so in a way that’s easy for anyone, even traditionally non-readers of poetry, to pick up and breathe in. Both poets are performance poets, having competed in various slam competitions and sharing their spoken word at events and in video, and they both utilized that skill in these books of poetry. There is an attention to language and sounds that sing to the reader, but it’s spent in more “plain” sentences, easy to read and understand and commit to memory. They don’t utilize as many of the techniques and aspects some may consider “high poetry,” such as complex metaphors or a high vocabulary, but show how even “plain” speaking can be poetry.

These poets are simply telling it how it is, which is so important when dealing with mental health. There is less stigma associated with it nowadays, but it’s still around. People are still afraid they are going to be misunderstood or judged if they speak about their mental illness; others will refuse to speak at all because it’s not something you talk about. These poetry books are doing important work within this conversation, this realm of discussion, by presenting poems that are poignant and linger in the mind, but are easy to read and devour. (This also means that these books are doing important work in the poetry realm as well, serving as an access point to those who may normally not read poetry. Both of these would serve well as a book you press into that friend’s hands and say why don’t you give this a try.)

Another thing I found interesting was the reoccurring theme of magic (not wizards and spells as much as magicians and shows) within these poems. Benaim has a five poem series entitled “magic trick,” as well as references in other poems and the title; Twohy has magic show centered poems “Shell Game” and “Zig-Zag Girl,” and also shows it in her cover art, which is designed to look like the book is a pack of cards being opened.

These intrigued me because when I was younger, I was obsessed with magic tricks, desperate to learn to impress friends and family and maybe, one day, complete strangers. But as I read these books, I realized how perfect this idea of magic was when talking about depression and anxiety. Magic tricks, at their core, are about illusion and misdirection. It doesn’t matter if you’re doing card tricks, or street magic, or sawing a woman in half, how you get away with it is that simple. Make it look like you’re doing one thing, then do another; keep the audience’s attention over here, while you truly do the trick over there.

Depression and anxiety are the magician, and you are the audience. They like to tell you that one thing is going on, when most likely it’s not, or not to the degree in which they are convincing you. They turn a simple slight of hand into a production so large you feel unable to deal with it. This is how they get you. In these books, however, Benaim and Twohy flip that script, show their speakers (you, the audience) doing the magic. Showing that you can live with your mental illness, you can have them be a part of you. And maybe you can make some magic along the way.

in some stories,

the protagonist has to kill the bad thing to release its light.

in my story,

i am the protagonist & the bad thing,

i have to learn how to bend the light out of myself.

i can do that magic.

(“on releasing light” by Sabrina Benaim)

Jordan E. McNeil writes, rages at videogames, and takes selfies with goats. Her work can be found in Jenny Magazine, Penguin Review, Rubbertop Review, and Willow: Women in Lit Lifting Other Women. She can be found on Twitter, @Je_McNeil.

Jordan E. McNeil writes, rages at videogames, and takes selfies with goats. Her work can be found in Jenny Magazine, Penguin Review, Rubbertop Review, and Willow: Women in Lit Lifting Other Women. She can be found on Twitter, @Je_McNeil.

Leave a Reply